|

|

||

|

|||

|

RELATED THEMES compensation health industry land livestock OTHER LOCAL THEMES BACKGROUND |

environment

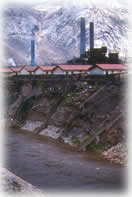

Some communities have had to relocate because the degradation had been so bad: "When the fumes [from the smelter] came we all dispersed, we had to leave because you couldn't live here any longer" (Peru 23). Of course the mines did bring infrastructure, income and jobs but, as several narrators point out, the work also engendered a different way of life and outlook, one unconnected with the environment: "[Miners] think of the present and that's all. They are trapped by their surroundings so... they don't think. That's what happens with contamination, they don't consider that it's going to affect the community later..." This narrator, like many comuneros struggling to make a living from the land, at one time took a job in the mines: "Unfortunately. I [too] felt more like a miner than a comunero, but then you think it over and you say, but this is my community and it's my land and you finally. do something about it, because.sometimes the damage they do to the land is irreparable" (Peru 14). Environmental controls have improved, but the legacy of past neglect is devastating. There is one agreement that Centromin has to return an area in La Oroya to its original state within 20 years, but local people are not optimistic. Some compensation battles have been successful, but often at disappointingly low levels; often the fight is beyond the means of communities. "We still haven't won a single case as I told you earlier, señor. We haven't got enough money to see us through a court case" (Peru 3). One teacher feels the mining interests are so powerful that local officials have been reluctant to implement effective research into levels of pollution or into environmental education campaigns: ".we don't get any further in having a serious, comprehensive study of the issue which would [also] cover education in the home.We have to find a way of getting over the overwhelming sense of resignation here" (Peru 32). One woman describes how ordinary people have been anything but resigned to the situation: "All the organisations in the community have joined together like I said. We stopped people from the mining camps in Huaymanta from going to work. Now we're doing their work by building a channel to take the waste waters away - to make people aware of what can be done. And we've formed groups. We don't let the big lorries go past - we stop them getting on with their work" (Peru 2). quotes about environment".at first there was no real awareness of the damage being done to the land. people believed what the company told them. They said.they were going to clean up the mess afterwards, that we shouldn't worry. Just lately the company said they were going to give the comuneros money and so the people took this into account and didn't speak out. They believed that with that money they could sort everything out. we had no idea of the damage, we weren't conscious of the true magnitude of the problem." "The hillsides of the mountain range were pure pasture so we were able to keep cattle and also plant crops.... But if you look around now... there's no land to be seen - there's a mountain there, but it's a mountain of pure rubbish from the mine." "When mining began in Cerro de Pasco they must have started to dump waste in the San Juan river.the trout disappeared. We could no longer drink the water and the animals got sick when they drank it. At first we thought it was a curse from God because we couldn't understand what had happened, because it changed the landscape. It's much worse now. If the water evaporates acid rain falls and burns the grazing land. We thought the land was exhausted until we understood what had happened." "Yes, the fumes give them torniquera, the sheep get sick from the fumes and start spinning round and round, like drunkards. When people go to La Oroya, down there by the foundry, when it's full of fumes it makes them sick, they get headaches, just like the animals. They begin going round and round, crying and doubling up in pain." "In old La Oroya they use to plant trees, they used to plant potato, oyucco (?), coca; it used to grow and there were trees, lots of trees, and different varieties too. [Now there aren't any, just] four or five little stumps here but they have been removed, you see." |

|

There is hardly a narrator whose life has not in some way been affected by the mining industry's pollution of the local environment. Rivers and streams have all been contaminated, affecting the health of people and animals. Some lakes have been drained in the search for minerals; others poisoned by industrial waste - fish and birds have disappeared. The pasture has been "scorched" by the toxic fumes, leaving livestock with neither pure grass or water, so they are "no longer getting fat". There has been a major increase in livestock disease, and among humans stomach and skin problems, teeth decay and respiratory disease are common. There have been social costs too:

There is hardly a narrator whose life has not in some way been affected by the mining industry's pollution of the local environment. Rivers and streams have all been contaminated, affecting the health of people and animals. Some lakes have been drained in the search for minerals; others poisoned by industrial waste - fish and birds have disappeared. The pasture has been "scorched" by the toxic fumes, leaving livestock with neither pure grass or water, so they are "no longer getting fat". There has been a major increase in livestock disease, and among humans stomach and skin problems, teeth decay and respiratory disease are common. There have been social costs too: